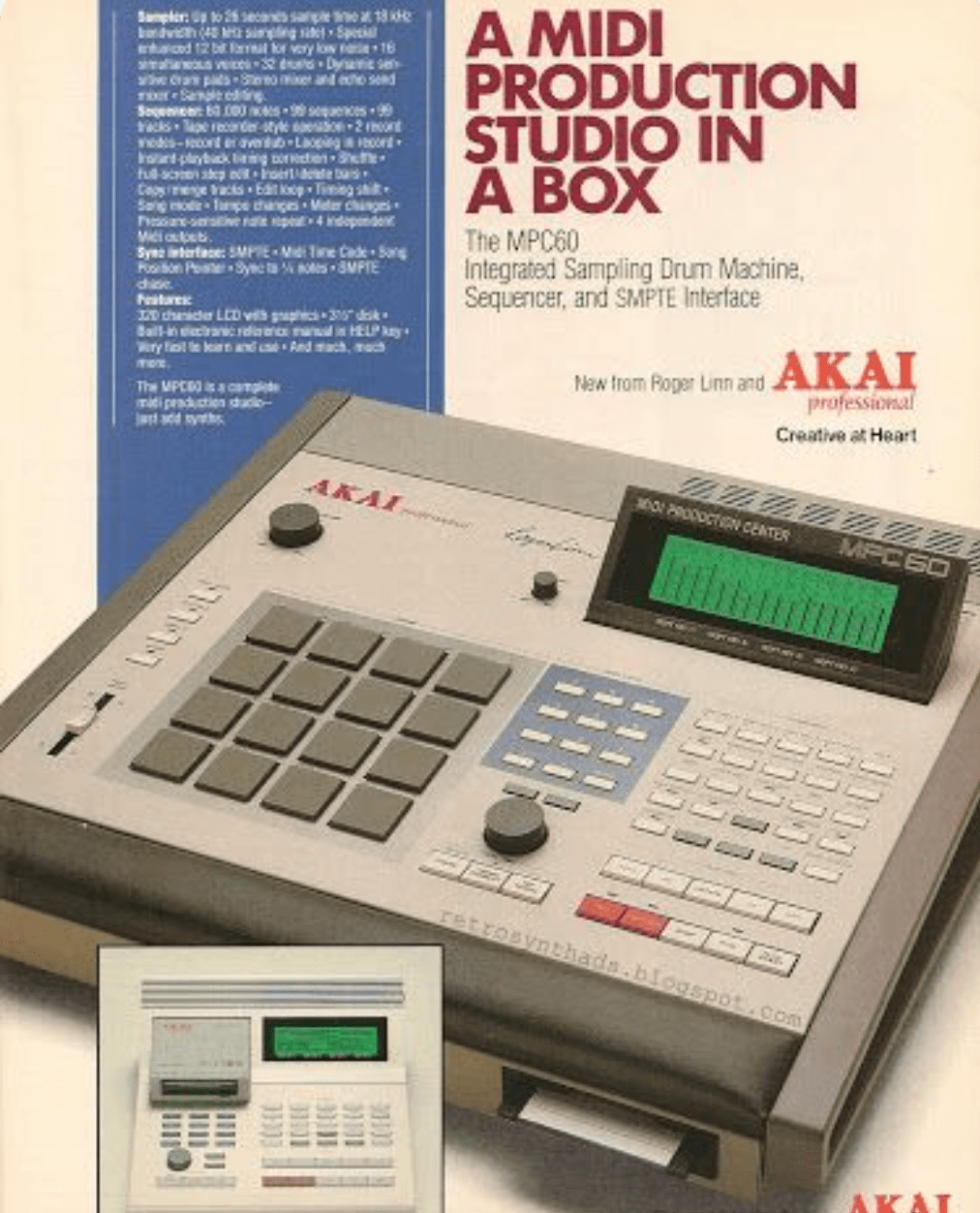

According to composer and journalist Kyle Gann, the musical note ceased to be the basic unit of musical composition sometime in the 1980s. In that decade, the advent of samplers (such as the Akai MPC60) made it possible to build pieces, rather than from notes, from any recorded sound complex. It’s a view Richard Taruskin recapitulates in his Oxford History of Western Music, which takes written notation as the enabling condition and unifying feature of Western art music, but ends with the “advent of postliteracy.” As Taruskin, citing Gann, argues, “the sampler frees composers from the habits inculcated by Western notation.”

Yet the 1980s witnessed the invention not only of digital samplers, but also of MIDI. MIDI – an acronym for Musical Instrument Digital Interface – was designed to enable synthesizers, regardless of manufacturer, to be linked together, primarily so that keyboard playing on one device could activate sound-generating capacities on another. Thanks to the cheapness of MIDI’s implementation, and the fact that its designers opted not to patent it, it was quickly adopted far and wide in digital music devices.

The result, according to technologist and musician Jaron Lanier, runs directly counter to the liberation narrative posited by Gann and Taruskin. “The whole of the human auditory experience has become filled with discrete notes that fit a grid,” Lanier writes. Rather than seeing digital music technologies emancipating musicians from the habits of Western notation, Lanier sees them delimiting and restricting the parameters of the note that notation had left fuzzy and flexible. “Before MIDI, a musical note was a bottomless idea that transcended absolute definition.…After MIDI, a musical note was no longer just an idea, but a rigid, mandatory structure you couldn’t avoid in the aspects of life that had gone digital.”

Did we become more firmly in thrall to notes than ever before, or more emancipated from their rule? Are our auditory worlds filled with “discrete notes that fit a grid,” or with rich “sound complexes”? Both Gann and Lanier posit a direct relationship between instrumental technologies and the very basis of musical construction. In their mirror-image narratives, Gann and Lanier thus agree on a fundamental. Stepping back, however, we can see that both take one tool as the basis for the whole musical world. (We might think of the cliché that when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.)

The issue here is not simply one of parts and wholes. Rather, there is a foundational issue having to do with narratives of technology in relation to musical thought and practice. Rather than think that any one tool becomes the whole musical world, we may find that there is a whole world in any musical tool.

Leave a reply to jeb54 Cancel reply