For most of his early career, Beethoven played on German and Viennese pianos. With the light action, clear attack, and rapid decay of these instruments, he composed themes such as this, from the concluding movement of Op. 49, No. 1:

Op. 49, No. 1 – Rondo: Allegro; Zvi Meniker playing a reproduction of an Anton Walter piano, c. 1790

In 1803, Beethoven received a new, French piano from the maker Sébastian Érard. This piano responded differently to his touch, used a foot pedal rather than knee lever to lift the dampers, and produced different sonorities. It was – as Tilman Skowroneck has discussed – a new tool with which to conceive musical ideas. With the less clear attack and longer decay of its tones, Beethoven explored new possibilities and abandoned old ones. One result was themes such as this, from the last movement of Op. 53 (the Waldstein Sonata):

Sonata No. 21, Op. 53 – Rondo: Allegretto moderato – Prestissimo, Bart van Oort playing a c. 1815 Salvatore Lagrassa piano

The long slurs, the slow pace of harmonic change, the rippling accompaniment in the right hand while the left hand alternates between resounding bass notes and treble-register theme, the bell-like quality of this theme – all are products of Beethoven’s interaction with his new Érard piano, the medium of his creative thought.

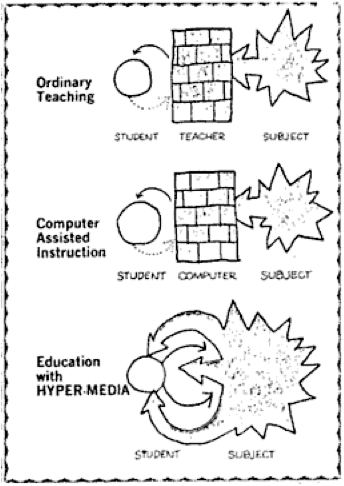

In “Personal Dynamic Media” (1977), Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg heralded a new “dynamic medium for creative thought” in the form of the Dynabook, a predecessor to the notebook computer.

Kay and Goldberg described the Dynabook as an active medium (or really, “metamedium” that can be all other media), which they saw as basically unprecedented. “For most of recorded history,” they wrote, “the interactions of humans with their media have been primarily nonconversational and passive in the sense that marks on paper, paint on walls, even ‘motion’ pictures and television, do not change in response to the viewer’s wishes.”

Yet the piano, and indeed all musical instruments, are responsive media. Some are more responsive than others – in 1796, Beethoven was dissatisfied with a Streicher-made piano because it “deprived him of the freedom to create my own tone.” But all musical instruments respond to the “queries and experiments” (to use Kay and Goldberg’s language) of their users.

Why did Kay and Goldberg exclude musical instruments from the prehistory of the Dynabook? Not out of neglect. As Kay and Goldberg state, “one of the metaphors we used when designing such a system was that of a musical instrument, such as a flute, which is owned by its user and responds instantly and consistently to its owner’s wishes.” Here, the reason for the exclusion becomes clear: Kay and Goldberg conceived musical instruments as interfaces, not as media.

Recently, Kay has suggested that musical instruments and computers belong to the same category. In a 2003 interview, he remarked, “the computer is simply an instrument whose music is ideas.” This sounds like a statement from a culture in which musical instruments are primarily vehicles for already composed music. It is as if music exists prior to instruments, simply waiting to be accessed. That musical instruments and computers are now the same for Kay may reflect the failure of one the dreams behind the Dynabook: the dream that everyone would become computer “literate.” Discussing the thinking behind the programming language he developed for the Dynabook, Kay explained, “the ability to ‘read’ a medium means you can access materials and tools generated by others. The ability to ‘write’ in a medium means you can generate materials and tools for others. You must have both to be literate.” The early environments developed using Kay’s language emphasized the “writing” side of literacy: they were for such activities as painting, animation, and composing. On the Dynabook, kids wouldn’t learn how to play a musical instrument – they would create their own musical instruments, and write music with them. With the Dynabook, Kay and Goldberg hoped, “acts of composition and self-evaluation could be learned without having to wait for technical skill in playing.”

But lets look at how Kay and Goldberg conceptualized media in 1977: “external media serve to materialize thoughts and, through feedback, to augment the actual paths the thinking follows.” That, to me, sounds like a good description of media. And it sounds like an excellent description of Beethoven’s Érard piano. Which should teach us that no technology can be a short-cut to our ideas; but any can be a medium for creative thought.